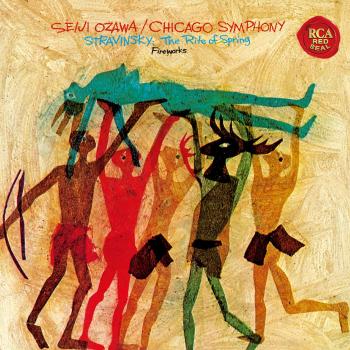

Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring (2025 Remastered) Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Seiji Ozawa

Album info

Album-Release:

1968

HRA-Release:

05.12.2025

Label: Sony Classical

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Seiji Ozawa

Composer: Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971): Fireworks, Op. 4 (2025 Remastered Version):

- 1 Stravinsky: Fireworks, Op. 4 (2025 Remastered Version) 03:32

- The Rite of Spring:

- 2 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Introduction (2025 Remastered Version) 03:09

- 3 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Harbingers of Spring (Dances of the Young Girls and Boys) (2025 Remastered Version) 03:09

- 4 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Mock Abduction (2025 Remastered Version) 01:22

- 5 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Spring Rounds (2025 Remastered Version) 03:33

- 6 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Games of the Rival Tribes (2025 Remastered Version) 01:48

- 7 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Procession of the Wise Elder (2025 Remastered Version) 00:40

- 8 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Adoration of the Earth (Wise Elder) (2025 Remastered Version) 00:20

- 9 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Dance of the Earth (2025 Remastered Version) 01:06

- 10 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Introduction (2025 Remastered Version) 04:27

- 11 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Mystic Circles of the Young Girls (2025 Remastered Version) 03:15

- 12 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Glorification of the Chosen One (2025 Remastered Version) 01:25

- 13 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Summoning of the Ancients (2025 Remastered Version) 00:53

- 14 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Ritual of the Ancients (2025 Remastered Version) 03:30

- 15 Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring: Sacrificial Dance (Chosen One) (2025 Remastered Version) 04:02

Info for Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring (2025 Remastered)

Masterpiece: Seiji Ozawa conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at the age of 32 for Stravinsky’s Harusai. In the late 1960s, the orchestra was in a period of decline under Jean Martinon, who succeeded Fritz Reiner, but in 1964 Ozawa became the music director of the Ravinia Festival and produced many recordings.

The Boston Symphony was at the peak of its powers when it engaged the 34-year-old Seiji Ozawa for this 1969 recording of Petrushka, in which the orchestra's then 24-year-old assistant conductor, Michael Tilson Thomas, played the extensive solo piano part. Ozawa, in those years, was capable of striking sparks with any orchestra he faced, and there is a palpable sense of excitement to the Petrushka he uncorks here. The accounts of The Rite of Spring and Fireworks, recorded in 1968 with the Chicago Symphony, are equally dynamic and colorful. BMG's long-awaited 24/96 remastering unleashes the breathtakingly open sound of the original tapes for the first time remastered in 24bit, and may require a volume cut to preserve peace with the neighbors." (Ted Libbey)

"By the end of the 1960s, less than 10 years after he'd won the Charles Munch competition at Besancon, Seiji Ozawa was the hottest young conductor in the world. Bernstein and Karajan became his mentors (sadly, the latter's influence was dominant by the early 1980s, and the result has been to weep over). In 1963 he was appointed music director of the Ravinia Festival, summer home of the Chicago Symphony after 1936. For the next five years he sustained morale and preserved the performance standard of Fritz Reiner (1953-62), while downtown Jean Martinon's tenure (1963-68) went from ecstasy to agony within the first season, and became increasingly embattled—but that's a story for another time and place. Concurrently, Ozawa was music director in Toronto, switching to San Francisco in 1970 for six euphoric seasons onstage and off. In 1970 he also became music director of the Tanglewood Festival, and in 1973 music director of the Boston Symphony—a post he will relinquish in 2002, to the relief of many players in the orchestra and not a few subscribers.

There were personal reasons for Ozawa going soft at the center that border on tragic; he was not, however, a Klemperer who suffered yet surmounted even worse private travail, nor even a Karajan, whose old age was a medical horror, complicated by the erosion of his three-decade dominance world-wide. However, until Ozawa became mealy he was a charismatic conductor and a brilliant interpreter of 20th-century music in particular. Stravinsky was a specialty early on, as these performances testify. The only unsubtle one is the brief Fireworks of 1908, despite the staggering virtuosity of Chicago's orchestra, equaled stateside at the time only by Eugene Ormandy's Philadelphians. This glitters, but doesn't sound as digested as the two ballet scores.

To protect the copyright, but also to trim his lavish 1911 instrumentation down to manageable size for performances by average-size orchestras, Stravinsky revised Petroushka in 1947. This reflected his allegiance to Neo-Classicism (which he claimed to have created after Sacre) until the ballet Agon 40 years later, and the subsequent embrace of Anton Webern's distillate of serialism. The piano part, for example, mainly for the second of the original Petroushka's four scenes, was greatly expanded in 1947. Of late, where orchestral budgets can afford extra players, we've heard a return to the 1911 original, altogether more colorful and in its way more subtle. Ideally one would have a copy of both, and I don't know a better version of 1947 than this one. The Boston Symphony played with a discipline Erich Leinsdorf restored after Charles Munch's dionysian reign. It has the bonuses of a November 1969 Symphony Hall recording without the usual reverberating hangover (credit the original producer Peter Dellheim and his engineer, Bernard Keville), and Michael Tilson Thomas as pianist, when he was the BSO's associate conductor.

The prize, though, is the blistering Chicago Sacre recorded downtown on July 1, 1968—Ozawa's final summer as music director at Ravinia. Although Orchestra Hall had been "renovated" in 1965 with appalling consequences acoustically, there'd been adjustments by 1968, and RCA knew where to place the orchestra for maximum effect without resorting to phony reverb. The sound, in BMG's 24 bit-rate/96 sampling-rate, leaps out at one—as if we shared the podium with Ozawa. It is the most persuasive, viscerally exciting demonstration of 24/96 remastering I've heard so far on any label. As for the interpretation, there are Sacres and there are Sacres (Stravinsky by the way favored "The Coronation of Spring" as an English translation of his full title), and several are staggeringly fine. But Ozawa's kinetic reading of 1968 holds its own, and the orchestra's breathtaking translation into sound nudges any super-digi-fi disc you care to name. As I listen, it tops the Oue/Minnesota Sacre on Reference Recordings, which I bought a few years ago at full price out of curiosity.

When persons speak of the Good Old Days, mine—in the wake of Reiner's semi-retirement and death—include the Ozawa summers at Ravinia, where he returned as a guest through 1971. And Sacre is surely the prize disc of that regime. In closing, BMG has all but obliterated RCA from its "High Performance" insert brochure; the only mention is "digitally remastered in BMG/RCA Studios, New York City." Does anyone else remember the Anschluss of 1938?

(Anent the spelling Petroushka—rather than Petrouchka—in the headnote and review, it was Stravinsky's own phonetic English spelling in those several books co-Crafted (by Robert, that is) in the late '50s. Petrouchka, still to be found in publicity releases, program books and CD literature, is the phonetic French spelling of Stravinsky's original Cryllic. The British have gone further yet. Gramophone spells it Petrushka, which is really too far. There's no "uh" in Petroushka, but neither is there an "ouch." It's allowable to think of the title as "Petrooshka," but how that would look? No, Stravinsky the painstaking multi-linguist, knew best— even though my insistence on Petroushka led to a recent divorce from the Seattle Symphony, where the p-r tail now wags the artistic dog, at least in matters of "promotion" and program book—the one place where it is possible to get things right, if anyone gives a damn. A few of us—who fell in love with semantics before there were computers with, God forbid, spell-checks—still do. We are, however, plainly a dying breed, destined to join the dodo and various sauri on the extinct list.)" (Classicalcdreview.com)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Seiji Ozawa, conductor

Recorded July 8, July 1, 1968; November 24, 1969 at Orchestra Hall, Chicago; Symphony Hall, Boston

Digitally remastered

Seiji Ozawa

Born 1935 in Shenyang, China. Seiji Ozawa studied piano from a young age, and after graduating from Seijo Junior High School, he went on to study conducting under Hideo Saito at the Toho School of Music.

In 1959, he won first prize at the International Competition of Orchestra Conductors held in Besançon, France, and was invited the next summer to Tanglewood by Charles Munch, who was a judge at the competition and music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the time. He proceeded to study under Karajan and Bernstein and went on to serve as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic, music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Ravinia Festival, music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and music director of the San Francisco Symphony. In 1973, he became the 13th music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, where his tenure of 29 years was the longest in the history of American orchestras.

As music director of BSO, he built the orchestra’s reputation nationally as well as internationally, with successful concerts in Europe in 1976 and Japan in March 1978. In March 1981, BSO toured 14 cities in America to commemorate its centennial and then executed a worldwide tour in fall of the same year, with stops in Japan, France, Germany, Austria, and the United Kingdom. It went on to perform in Europe in 1984, 1988, and 1991, and Japan in 1986 and 1989, all to great acclaim.

In 1978, Ozawa was officially invited by the Chinese government to work with the China Central Symphony Orchestra for a week. A year later in March 1979, Ozawa visited China again, this time with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In addition to orchestra performances, he facilitated significant cultural and musical exchanges through discussions and teaching sessions with Chinese musicians. He has since continued to build a strong relationship with China.

In autumn 2002, Ozawa became music director at Wiener Staatsoper, a position he held until spring 2010. His reputation and popularity are enormous in Europe, where he has conducted many orchestras including the Berliner Philharmoniker and the Vienna Philharmonic. He has also appeared in prominent opera houses such as Wiener Staatsoper in Vienna, l’Opéra National de Paris, Teatro alla Scala in Milan, Opera di Firenze, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In Japan, Ozawa formed the Saito Kinen Orchestra with Kazuyoshi Akiyama in 1984 to commemorate their late mentor, Hideo Saito. The orchestra held greatly successful concerts in Tokyo and Osaka and went on to tour Europe in 1987, 1989, and 1990. In 1991, it performed concerts in Europe and America and was received with great accolades. These activities lead to the inception of Ozawa’s artistic dream in 1992: the Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto. Ozawa became director of this international music festival, a role that continues to this day. SKO continued to tour, with overseas concerts in 1994, 1997 and 2004. From 2015, the festival has entered a new stage as the “Seiji Ozawa Matsumoto Festival”.

Ozawa has been particularly focused on education. The Chamber Music Academy Okushiga had evolved from the Saito Kinen chamber music study group sessions that started in 1997, and in 2011, this became the non-profit organization Ozawa International Chamber Music Academy Okushiga, Asia, to provide opportunities to outstanding students from countries in the region. Ozawa also founded the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy Opera Project in 2000 and the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy Orchestra Project in 2009, working actively to cultivate young musicians through performance. In 2005, he established the Seiji Ozawa International Academy Switzerland to educate European music students. Ozawa has also worked closely with the Mito Chamber Orchestra since its founding in 1990, serving as general director of the orchestra as well as director general of Art Tower Mito from 2013. He has also worked regularly with the New Japan Philharmonic since its founding.

Ozawa has won many awards in Japan and abroad, including: the Asahi Prize (1985); an Honorary Doctorate from Harvard University (2000); the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, First Class (2002); the Mainichi Art Award (2003); the Suntory Music Prize (2003); an Honorary Doctorate from the Sorbonne University of France (2004); Honorary Membership from the Wiener Staatsoper (2007); France’s Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (2008); Foreign Associated Member in the Académie des Beaux-Arts de l’Institut de France (2008); the Order of Culture, which is the highest honor in Japan (2008); Giglio D’Oro by Premio Galileo 2000 Foundation of Italy (2008); the first Japanese national to be bestowed honorary membership to the Vienna Philharmonic (2010); the Praemium Imperiale from the Japan Art Association (2011); the Akeo Watanabe Foundation Music Award (2011); and the Kennedy Center Honors (2015). In February 2016, the Ravel L’enfant et les sortilèges album conducted by Seiji Ozawa and performed by the Saito Kinen Orchestra that was recorded at the 2013 Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto won the 58th Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. In April 2016, he was named an Honorary Member of the Berliner Philharmoniker.

This album contains no booklet.