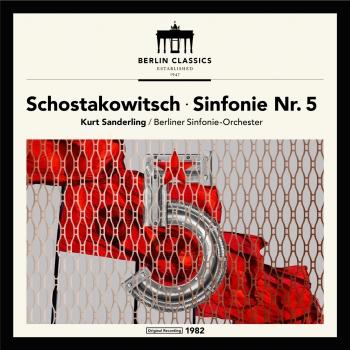

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47 Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester & Kurt Sanderling

Album info

Album-Release:

1992

HRA-Release:

17.05.2016

Label: Berlin Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester & Kurt Sanderling

Composer: Dmitri Schostakowitsch (1906-1975)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- 1 I. Moderato - Allegro non troppo 17:37

- 2 II. Allegretto 05:33

- 3 III. Largo 15:34

- 4 IV. Allegro non troppo 11:53

Info for Shostakovich: Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47

That Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony had an “emotional subtext” (2) was clear to Kurt Sanderling when he attended the acclaimed Moscow first performance of the work in January 1938. As he has often related, he had the impression he could be imprisoned for having heard the music. And yet the symphony had ended in such seeming triumph – so that it was obvious the composer had addressed his listeners in what has been called “Aesopian” language: coded and multiply ambiguous. The encoding was necessary because what had to be said could not be said openly. There were and still are misunderstandings about the actual content of the score. Aware of these problems, Kurt Sanderling made it his life’s mission to defend Shostakovich’s symphonic works against false and misleading interpretation. Contemporaries who had taken part in the present recording were still at hand to offer their own views. …

Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester

Kurt Sanderling, Dirigent

Recorded January 1982 Berlin, Studio Christuskirche

Digitally remastered

Kurt Sanderling

Having studied initially in Königsberg, the capital city of East Prussia (now called Kaliningrad, and located in Russia) and in Berlin, Kurt Sanderling was engaged as a répétiteur in 1931 by the Berlin Städtische Opera, where he assisted Fritz Stiedry and Paul Breisach. However, with the assumption of power by the National Socialist regime in 1933 he was compelled to give up this position, and worked subsequently with the Berlin Jewish Cultural Federation leaving Germany as a refugee in 1936. Unusually for a musician, instead of heading west, Sanderling travelled to the east, where he had relatives. He secured a post as assistant to Georges Sébastian with the Moscow Radio Orchestra and made his conducting début with the orchestra in 1937. He left Moscow in 1939 to become chief conductor with the Kharkov Philharmonic Orchestra, a position which he retained for three years.

Having made a guest appearance with Evgeny Mravinsky’s Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra in 1941, Sanderling was invited to become this orchestra’s second conductor at a time when it had been evacuated to Novosibirsk, Siberia, a situation conducive to his forming a close relationship with his musical colleagues. The orchestra returned to Leningrad in 1944 and Sanderling and Mravinsky shared the principal conducting duties (with Mravinsky in charge) until 1960; during this period Sanderling also taught conducting at the Leningrad Conservatory. In 1960 the Communist authorities invited him to return to East Berlin to become chief conductor of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra, with the intention of making this orchestra a rival to the Berlin Philharmonic, then under the direction of Herbert von Karajan. This objective Sanderling to a large extent achieved, making numerous recordings for the East German record company VEB with both the Berlin Symphony Orchestra and with the Dresden Staatskapelle, of which he was chief conductor from 1964 to 1967.

During the 1960s Sanderling appeared abroad, making successful appearances at the festivals of Prague, Salzburg, Vienna and Warsaw. He made his début in the United Kingdom with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1970 and in 1972 substituted for Otto Klemperer with the New Philharmonia Orchestra, with whom he developed a close relationship. He recorded a complete cycle of the Beethoven symphonies with this orchestra in 1981 and was made an honorary member in 1996, the only previous recipient of this award being Klemperer. He conducted the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra for the first time in 1976 in a sequence of outstanding performances which led to subsequent appearances with the orchestra in 1978, 1980 and 1990. Following the collapse of the Communist regime, during the 1990s Sanderling enjoyed a distinguished international career, and gave notable performances with many leading orchestras, including the Royal Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Los Angeles Philharmonic. In 2002, the year of his ninetieth birthday, he decided to cease conducting.

Sanderling was a true representative of the Austro-German style of conducting, and at the same time, because of his extensive experience in Soviet Russia, an authoritative interpreter of twentieth-century composers such as Shostakovich. His podium manner was undemonstrative, with an expansive but always clear baton technique. In rehearsal however he was highly dynamic, as the writer Norman Lebrecht graphically illustrated in connection with the preparation for a performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 8 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in 1991: ‘Restrained and energy-efficient on the concert podium, he becomes a different man in rehearsal, loquacious to the point of garrulousness, acting up like a Hollywood ham in a surging current of communication. When a flute and harp fail to grasp his intentions, he detains them at the end of the session, pacing wordlessly back and forth until the players comprehend the weariness and boredom he is trying to make them convey.’

Sanderling’s recorded repertoire is very wide indeed, and includes complete cycles of the symphonies of Brahms and Sibelius, both of which are outstanding. His recordings of the music of Bruckner and Mahler are equally notable. His recordings of Shostakovich, especially of Symphonies Nos 5, 6, 8, 10 and 15, and of Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2, with the Leningrad Philharmonic, may be considered authoritative; while his accounts of the final three Tchaikovsky symphonies are extremely powerful, in a more Teutonic sense. By contrast his interpretations of Haydn’s six ‘Paris’ symphonies are full of wit and elegance. Sanderling was also a most distinguished accompanist, recording with such leading instrumentalists of the Soviet Union as Emil Gilels and David Oistrakh. His account of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter is deeply poetic.

Kurt Sanderling died on 17 September 2011, two days before his 99th birthday.

Booklet for Shostakovich: Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47