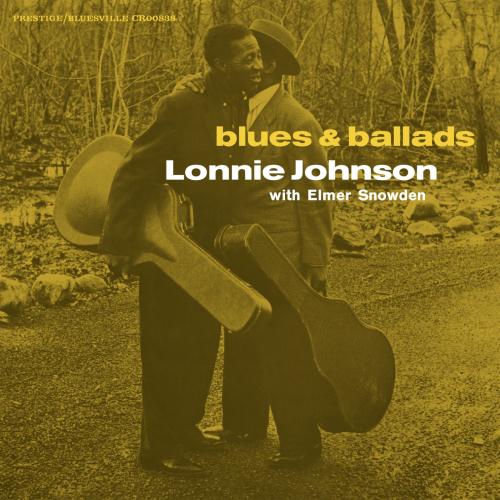

Blues & Ballads (Remastered 2025) Lonnie Johnson

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

1960

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

14.03.2025

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Haunted House (Remastered 2025) 05:02

- 2 Memories Of You (Remastered 2025) 04:21

- 3 Blues For Chris (Remastered 2025) 05:07

- 4 I Found A Dream (Remastered 2025) 04:34

- 5 St. Louis Blues (Remastered 2025) 03:06

- 6 I'll Get Along Somehow (Remastered 2025) 04:28

- 7 Savoy Blues (Remastered 2025) 04:12

- 8 Back Water Blues (Remastered 2025) 05:05

- 9 Elmer's Blues (Remastered 2025) 03:29

- 10 Jelly Roll Baker (Remastered 2025) 04:16

Info zu Blues & Ballads (Remastered 2025)

Der in New Orleans geborene Lonnie Johnson war wahrscheinlich einer der musikalisch anspruchsvollsten Bluesgitarristen. Lonnie Johnsons Vermächtnis ist immens, nicht nur im Bluesbereich. Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, LaVern Baker, Bob Dylan und unzählige andere haben seine Songs aufgenommen. Er hat einen unauslöschlichen Eindruck in der modernen amerikanischen Musik hinterlassen. Wie bei anderen Bluesmusikern seiner Generation ging auch bei Lonnie Johnson seine musikalische Aktivität in den 1950er Jahren zurück, sodass er nur noch als Koch oder Hausmeister arbeitete. „Blues & Ballads“ ist eines der Alben, die sein Comeback markierten.

Lonnie Johnson, E-Gitarre, Gesang

Elmer Snowden, Akustikgitarre

Wendell Marshall, Kontrabass

Aufgenommen am 5. April 1960 im Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Tontechnik: Rudy Van Gelder

Produktion: Chris Albertson

Digital remastered

Zur Info: wir bieten die 192 kHz-Version nicht an, denn in unserer Messanalyse konnten wir keinen nennenswerten bzw. hörbaren Mehrwert zu der 96 kHz-Version feststellen!

Alonzo "Lonnie" Johnson

(February 8, 1899 – June 16, 1970) was an American blues and jazz singer, guitarist, violinist and songwriter. He was a pioneer of jazz guitar and jazz violin and is recognized as the first to play an electrically amplified violin.

Johnson was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, and raised in a family of musicians. He studied violin, piano and guitar as a child and learned to play various other instruments, including the mandolin, but he concentrated on the guitar throughout his professional career. "There was music all around us," he recalled, "and in my family you'd better play something, even if you just banged on a tin can."

Johnson pioneered the single-string solo guitar styles that have become customary in modern rock, blues and jazz music.

By his late teens, he was playing guitar and violin in his father's family band at banquets and weddings, alongside his brother James "Steady Roll" Johnson. He also worked with the jazz trumpeter Punch Miller in the Storyville district of New Orleans.

In 1917, Johnson joined a revue that toured England, returning home in 1919 to find that all of his family, except his brother James, had died in the 1918 influenza epidemic.

He and his brother settled in St. Louis in 1921, where they performed as a duo. Lonnie also worked on riverboats and in the orchestras of Charlie Creath and Fate Marable.

In 1925 Johnson married, and his wife, Mary, soon began a blues career of her own, performing as Mary Johnson and pursuing a recording career from 1929 to 1936. (She is not to be confused with the later soul and gospel singer of the same name.) As with many other early blues artists, information on Mary Johnson is often contradictory and confusing. Various online sources give her name before marriage as Mary Smith and state that she began performing in her teens. However, the writer James Sallis gave her original name as Mary Williams and stated that her interest in writing and performing blues began when she started helping Lonnie write songs and developed from there. The two never recorded together. They had six children before their divorce in 1932.

In 1925, Johnson entered and won a blues contest at the Booker T. Washington Theatre in St. Louis, the prize being a recording contract with Okeh Records.To his regret, he was then tagged as a blues artist and later found it difficult to be regarded as anything else. He later said, "I guess I would have done anything to get recorded – it just happened to be a blues contest, so I sang the blues." Between 1925 and 1932 he made about 130 recordings for Okeh, many of which sold well (making him one of the most popular OKeh artists). He was called to New York to record with the leading blues singers of the day, including Victoria Spivey and the country blues singer Alger "Texas" Alexander. He also toured with Bessie Smith, a top attraction of the Theater Owners Bookers Association.

In December 1927, Johnson recorded in Chicago as a guest artist with Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, paired with the banjoist Johnny St. Cyr. He played on the sides "I'm Not Rough", "Savoy Blues", and "Hotter Than That." In an unusual move, he was invited to sit in with many OKeh jazz groups. In 1928 he recorded "Hot and Bothered", "Move Over", and "The Mooche" with Duke Ellington for Okeh. He also recorded with a group called the Chocolate Dandies (in this case, McKinney's Cotton Pickers). He pioneered the guitar solo on the 1927 track "6/88 Glide", and on many of his early recordings he played 12-string guitar solos in a style that influenced such future jazz guitarists as Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt and gave the instrument new meaning as a jazz voice. He excelled in purely instrumental pieces, some of which he recorded with the white jazz guitarist Eddie Lang, with whom he teamed in 1929. These recordings were among the first to feature black and white musicians performing together, although Lang was credited as Blind Willie Dunn to disguise the fact.

Much of Johnson's music featured experimental improvisations that would now be categorised as jazz rather than blues. According to the blues historian Gérard Herzhaft, Johnson was "undeniably the creator of the guitar solo played note by note with a pick, which has become the standard in jazz, blues, country, and rock". Johnson's style reached both the Delta bluesmen and urban players who would adapt and develop his one-string solos into the modern electric blues style. However, the writer Elijah Wald declared that in the 1920s and 1930s Johnson was best known as a sophisticated and urbane singer rather than an instrumentalist: "Of the forty ads for his records that appeared in the Chicago Defender between 1926 and 1931, not one even mentioned that he played guitar."

Johnson's compositions often depicted the social conditions confronting urban African Americans ("Racketeers' Blues", "Hard Times Ain't Gone Nowhere", "Fine Booze and Heavy Dues"). In his lyrics he captured the nuances of male-female love relationships in a way that went beyond Tin Pan Alley sentimentalism. His songs displayed an ability to understand the heartaches of others, which Johnson saw as the essence of his blues.

After touring with Bessie Smith in 1929, Johnson moved to Chicago and recorded for Okeh with the stride pianist James P. Johnson. However, with the temporary demise of the recording industry in the Great Depression, he was compelled to make a living outside music, working at one point in a steel mill in Peoria, Illinois. In 1932 he moved again, to Cleveland, Ohio, where he lived for the rest of the decade. There he performed on radio programs and intermittently played with the band backing the singer Putney Dandridge.

By the late 1930s, he was recording and performing in Chicago for Decca Records, working with Roosevelt Sykes and Blind John Davis, among others. In 1939, during a session for Bluebird Records with the pianist Joshua Altheimer, Johnson used an electric guitar for the first time. He recorded 34 tracks for Bluebird over the next five years, including the hits "He's a Jelly Roll Baker" and "In Love Again".

After World War II, Johnson made the transition to rhythm and blues, recording for King in Cincinnati and having a hit in 1948 with "Tomorrow Night" written by Sam Coslow and Will Grosz. The topped the Billboard Race Records chart for 7 weeks and reached number 19 on the pop chart with sales of three million copies. A blues ballad with piano accompaniment and background singers, the song bore little resemblance to much of Johnson's earlier blues and jazz material. The follow-ups "Pleasing You", "So Tired", and "Confused" were also R&B hits.

In 1952 Johnson toured England. Tony Donegan, a British musician who played on the same bill, paid tribute to Johnson by changing his name to Lonnie Donegan. Johnson's performances are thought to have been received poorly by British audiences; this may have been due to organizational problems with the tour.

After returning to the United States, Johnson moved to Philadelphia. He worked in a steel foundry and as a janitor. In 1959 he was working at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel in Philadelphia in 1959 when WHAT-FM disc jockey Chris Albertson located him and producedBlues by Lonnie Johnson for Bluesville Records. This was followed by other Prestige albums, including one (Blues & Ballads) with the former Ellington boss Elmer Snowden, who had helped Albertson locate Johnson. Snowden had been the original bandleader of the Washingtonians, which Ellington took over after Snowden vacated the position and made into the famous Ellington orchestra. There followed a Chicago engagement for Johnson at the Playboy Club. This succession of events placed him back on the music scene at a fortuitous time: young audiences were embracing folk music, and many veteran performers were stepping out of obscurity. Johnson was reunited with Duke Ellington and appeared as a guest at an all-star folk concert.

In 1961, Johnson was reunited with his Okeh recording partner Victoria Spivey for another Prestige album, Idle Hours, and the two singers performed at Gerdes Folk City. In 1963 he toured Europe as part of the American Folk Blues Festival with Muddy Waters and others and recorded an album with Otis Spann in Denmark.

In May 1965, he performed at a club in Toronto before an audience of four people. Two weeks later, his shows at a different club attracted a larger audience, and Johnson, encouraged by Toronto's relative racial harmony, decided to move to the city. He opened his club, Home of the Blues, on Toronto's Yorkville Avenue in 1966, but it was a business failure, and Johnson was fired by the man who became owner. Through the rest of the decade, he recorded, played clubs in Canada, and embarked on several regional tours.

In March 1969 he was hit by a car while walking on a sidewalk in Toronto. He was seriously injured, suffering a broken hip and kidney injuries. A benefit concert was held on May 4, 1969, with two dozen acts that included Ian and Sylvia, John Lee Hooker, and Hagood Hardy. He never fully recovered from his injuries and suffered what was described as a stroke. He was able to return to the stage for one performance at Massey Hall on February 23, 1970, walking with the aid of a cane, to sing a couple songs with Buddy Guy; Johnson received a standing ovation.

Johnson died on June 16, 1970. A funeral was held at Mount Hope Cemetery in Toronto by his friends and fellow musicians, but his family members insisted on transferring the body to Philadelphia where he was buried. He was "virtually broke." The Killer Blues Headstone project, a nonprofit organization that places headstones on unmarked graves of blues musicians, purchased a headstone for Johnson around 2014.

In 1993, Smithsonian Folkways released The Complete Folkways Recordings, an anthology of Johnson's music, on Folkways Records. He had been featured on several compilation blues albums from Folkways, beginning in the 1960s, but never released a solo album on the label in his lifetime.

Johnson was posthumously inducted into the Louisiana Blues Hall of Fame in 1997.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet